Back to Burnley: “It‘s not just prayer we need to tackle poverty.”

A couple of weeks ago the results of the latest UK census revealed that the number of people who say they have no religion has increased to 37.2% of the population. That evening the BBC’s Question Time panel were asked whether “belief in God is now an outmoded belief”. The responses varied a little but the replies essentially followed a template of ‘religion is private’ and ‘politics and belief’ are separate. But are they? If anyone needs proof of the public and political impact religion or belief play in the lives of our wider communities then one doesn’t need to look any further than Burnley, Lancashire and the faith-inspired and informed work of two remarkable people: Bishop Mick Fleming and Father Alex Frost. They along with the members of their communities featured in a series of award-winning BBC news films chronicling the darkest days of the pandemic and the impact COVID and poverty have had on one of the UK’s most vulnerable communities. They are remarkable people doing remarkable work. You can hear them talking about it and the impact the media coverage has had on our events page.

Now, it is obviously entirely possible for one to behave ethically without having religion. And it’s also true that religion can be found at the core of some prejudices, bigotry and conflict. But to ignore the role religious belief, religious communities and “people of faith” have played and continue to play in the battle for social justice, tolerance and wider community, is wrong.

Father Alex Frost is right: it takes more than prayer to tackle poverty and injustice but prayer or the will to make a difference, translated into action is a start.

The column below was written by Fr Alex Frost and originally appeared in The Big Issue magazine. which exists to give homeless and long-term unemployed and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. Details of how to support their work are at the bottom of the page.

by Father Alex Frost, December 2022

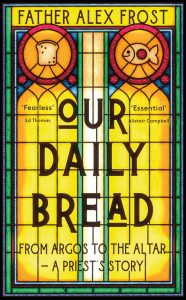

In 1993, I was a football referee officiating in the local Sunday league. I’d just been terribly assaulted by a player because I’d sent him off. As I lay flat out with a bloodied nose and a black eye, I could never have imagined that in autumn 2022 I’d be a published author writing about poverty, addiction and people experiencing homelessness. In 2010, as I performed my own stand-up comedy to a sold-out venue to raise funds for disabled children, I never dreamed that one day I would work on a BBC documentary about the cost-of-living crisis. Had I known, I would have laughed harder than the audience before me. And if I’d been told as I left Argos in 2015 after nearly 20 years as a store manager for a position as a minister in the Church of England, that my book Our Daily Bread: From Argos to the Altar would be on the shelves of bookshops nationwide seven years later, I would think someone was taking the proverbial.

In October 2022 that’s exactly what happened. Telling the real-life stories of people in my hometown of Burnley has been the biggest privilege of my life. Stories such as Mark’s, who has been an addict for as long as he can remember, experiencing homelessness for much of his life, ignored by social services and written off as hopeless and incurable.

Stories written into chapters such as “Jenny Swears a Lot” – aptly named because she really does swear a lot and refuses to make concessions with her language for anyone, including a priest such as myself. A lady who tells it as it is and deals with her feelings and experiences of unfairness and injustice with a typical working-class Lancashire approach of “It’ll be reet”, meaning she will just crack on regardless of what life throws at her.

And stories of the Devlin family, who lost their young daughter Kelsey during the pandemic while on a trip to Pakistan. Kelsey died and was buried in Islamabad before the family knew she had passed away. On seeking answers, they only found a backdrop of apathy, disillusionment and injustice.

Through my own journey of being a prolific schoolboy truant, to a teenager suffering from obsessive compulsive disorder, to being a damaged and retired football referee, stand-up comedian, to an Argos store manager, then finally to a Church of England vicar I am reminded we all have the capacity to change and to be changed.

In my book I challenge the reader to consider change and how that comes about. When I first met Mark at my church, St Matthew’s with Holy Trinity in Burnley, the first thing he said to me was: “Vicar, can you help me? I’m f*****g drowning. I’m homeless, I’m an addict and I don’t want to live like this any more.” From that conversation a few years ago, an interesting relationship ensued. I’d love to be telling you that two years later Mark was in recovery, that his life was transformed, and he was in a much better place.

Well, it has changed but not yet enough to rejoice and celebrate. Mark is no longer homeless; he lives in a hostel. Mark is still addicted to alcohol, he recently tried to detox, but he was soon back in his familiar surroundings of nine per cent strong beer and a community of people with similar issues of sofa surfing and addiction. Even a vicar full of prayer for Mark can’t transform him or people like him and the situations they find themselves in. It’s not just prayer that’s required, but a revolution in care and treatment of those people who live in poverty. That’s what I call for in my book.

Poverty is not just about money; poverty is so much more. I want to challenge the poverty of compassion, love and empathy. A poverty of love and concern for our neighbour, a poverty of political aspiration to affect change and to finally bring an end to homelessness, foodbanks and chronic life-threatening issues surrounding addiction.

Through my own experiences of change, I must be hopeful that others can change as well, both those who are suffering and those who can make a difference. I call upon councils, county councils, Westminster, politicians and beyond to be the change we need them to be. To hold every individual as important, valued and worthy of investment. Investment of time, money and opportunity.

My life experiences are laid out in this book. I can’t go back and change them, nor would I want to, and none of us can change what happened to us yesterday. But we can all influence what happens tomorrow. If society wants to, it can change, the question for us all is how much do we want it?

Father Alex Frost is the vicar at St Matthew’s the Apostle church in Burnley where he grew up. You can donate to or find out more about their work here. And you can meet some of the people from his community, among a range of better known public figures, in his podcast, called “The God Cast“, where Fr Alex interviews interesting people about their lives and belief.