Broadcasters have immense influence when it comes to informing how audiences understand the world. What we see on our screens or hear on through our speakers can influence not only how we see others but also how we see ourselves. At the Sandford St Martin Trust we have long argued that this is why representation really matters. And in a world where 85% of the population identify with a religion, it’s why representations of people of different faiths also matter. Accurate or fair representation helps break down barriers, promotes understanding, introduces us to new ideas and perspectives and helps mitigate prejudice and bigotry.

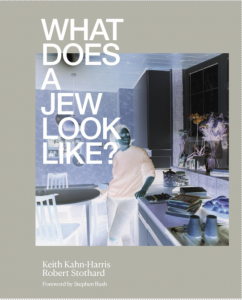

Keith Kahn-Harris is a sociologist and the author of What Does A Jew Look Like? which will be launched at an event at JW3 London on 11 April, 2022. He has also done us the honour of agreeing to both help judge our 2022 TV/Video Award and writing a blog on the subject of representation here.

Beyond black hats and stereotypes: Jews and the visual image

by Keith Kahn-Harris

7 April 2022

Jews have blessings for everything, from mundane everyday activities such as eating and drinking, to events that very rarely happen. One of the latter is the blessing to be recited on seeing 600,000 Jews together:

Blessed are You, LORD, our God, King of the Universe, knower of secrets.

600,000 is the number of Jews who stood at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah. The rationale for this prayer is given in the Talmud:

Why [do we say this particular blessing]? [God] sees a whole nation whose minds are unlike each other and whose faces are unlike each other … and God knows what is in each of their hearts….

The prayer and its rationale suggest that, even when large numbers of Jews – or anyone else – are gathered together in a mass, they remain irreducibly unique. Only God can really make sense of that heap of individuality.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen 600,000 people together in one place, Jews or otherwise. Outside of events like football matches and demonstrations, most of us we live in a world where we only ever see a handful of people at any one time. That creates a challenge: How do we grasp the reality of entire categories of people when we cannot actually ‘see’ them? While we are all unique, we do share collective identities and other characteristics that bind us together in some way, even if only God can truly grasp the whole.

One of the ways we ‘see’ groups is through stereotypes. A stereotype allows us to see individuals as macrocosms of something bigger. Insofar as members of certain groups may look similar to each other or dress in a certain way, stereotypes can be useful to a degree. But not only can stereotypes be wielded for hateful purposes, they can also blind us to the diversity of a certain group.

For some years now, I have been fascinated by the ways in which stereotypical images of strictly orthodox Jewish men – complete with beards, black coats and black hats – are used as a visual shorthand for all Jews. In the British media, stock photos of strictly orthodox Jews are routinely used to illustrate any kind of story about Jews, even when they don’t concern that type of Jew at all.

Jews, of course, are many different things: Orthodox, progressive and secular; Ashkenazi, Mizrachi and Sephardi; straight, cis and LGBT; and so on. That diversity constitutes a visual ‘problem’. How do you grasp the fact that being Jewish can mean many contradictory things in one photo? You probably can’t, but that doesn’t mean that the need for visual images is any less. In newspapers today, almost every story is illustrated for online use; so which one to choose? Strictly orthodox Jews make a kind of sense here, first because they are strikingly ‘different’ and recognisable, and also because they seem to be the ‘most Jewish’ of Jews.

Of course, there are a lot of myths that circulate about strictly orthodox Jews, sometimes known as Haredi Jews. They are not an unchanging throwback to how Judaism has always been. In fact, this kind of Judaism was an innovative response to the challenges of Jewish emancipation in the post-Enlightenment world. Whereas other sorts of Jews sought to enter the wider world as soon as they had the opportunity, what became known as Haredi Jews sought to create a community that would be insulated from the threat of external temptation. As such, they have been successful, recovering demographically after the Holocaust with a very high birth rate and ensuring that a large proportion of its members remain in fulltime Torah study throughout their lives.

Nor are Haredi Jews monolithic. The community is replete with competing sects and ideological tensions. While, to outsiders, their dress seems uniform, there are numerous subtle differences in clothing style that are meaningful to insiders. And while Haredi women are sometimes invisible in the media, their position in the community isn’t as simple as it sometimes seen; in the UK for example, Haredi women are prominent amongst the leaders of their welfare charities.

So treating Haredi Jews as generic Jews erases their diversity, just as it erases other sorts of Jews. We badly need a more complex visual language to represent who Jews are.

My own contribution to this project has been to work with Rob Stothard, the (non-Jewish) photographer who took one of the most recognisable stock photos of Haredi Jews (this one), to create a more heterogeneous set of photographic images of Jews living in Britain. In our book, What does a Jew look like?, we have assembled an assortment of portraits of British Jews that emphasise not just the diversity of the population, but also the idiosyncracy of individual Jewish lives. To that end, each portrait is accompanied by a ‘self-portrait’ in the subject’s own words.

The book does contain portraits of Jews that are either Haredi or adjacent to that particular Jewish community. However, they come across as Jewish individuals, rather than as stereotypes. Yael, for example, is no one’s idea of a generic Jew:

Yael is part of the Chabad/Lubavitch sect and is married to a rabbi. She comes from an Iraqi Jewish family and works in finance. You would be forgiven for not realising that, in the photo, she is actually wearing a sheitel, a wig used by orthodox Jewish women to cover their hair.

Such non-stereotypical images create both an opportunity and a challenge. The opportunity is to come to understand Jewish life as a complexity of Jews; the challenge is to find a way to do that whilst acknowledging that, sometimes at least, one image must stand for the whole. Hopefully, What does a Jew look like? will encourage conversation on these issues, which do not apply just to Jews, but to most other ethno-religious groups.

What does a Jew look like? is published by Five Leaves Books. It will be launched at an event at JW3 London on 11 April, 2022.